Carl Sandburg might have described Malbec as big-shouldered, stormy, husky and brawling. He might have called it coarse and strong and cunning. One thing is clear: Whether in its juicy, gentle incarnation in the Southwest of France or in its more tannic, voluminous and generous New World guise, Malbec is built to last.

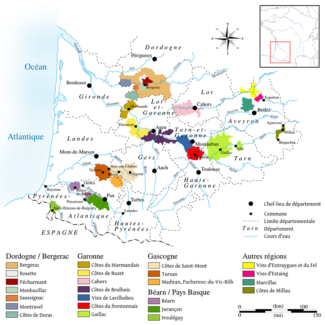

At one time, Malbec was planted so widely across France that it has a thousand different regional names. In recent years, the somewhat austere quality of the wine and its sensitivity of the vines to frost and mildew have greatly reduced its overall acreage, although 11% of the world’s Malbec may still be found in Cahors. In Argentina, where it was first planted in 1868, it has become not only the country’s signature variety but the most widely grown red grape, with more than 77,000 acres planted to Malbec. In the foothills of the Andes—especially in the high-altitude regions of Luján de Cuyo and the Uco Valley—Malbec achieves an elevated status of its own. The drier atmosphere of the mountains all but eliminates the mildew scourge to which it is susceptible near sea level, and the limestone rich soils (notably in Gualtallary, Altamira and La Consulta) have helped built an international reputation for age-worthy gems that are also approachable in their youth.

Despite the fashionable acclaim that South American Malbec has earned, the medieval city of Cahors in Southwest France will always be its spiritual home. First planted by the Romans and known locally as Côt or Auxerrois, the Malbec grape must make up a

minimum of 70% of any wine bearing the Appellation ‘Cahors’ on the label, with permissible blending grapes restricted to Tannat and Merlot—Cahors is unique in Southwest France in that it prohibits the use of Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. Since Malbec does not fully ripen until October, Cahors tends to be a September-driven wine and conditions the month before largely determine the success of the harvest. In lesser years, tannins compete with an acidic assault and dominate the palate. But in fine vintages like 2015 and 2018, the wine is a nice balance of rich wood and herbal fruit with dark chocolate and licorice flavors sidling in behind softer tannins. This holds especially true for the new generation of Cahors producers, who have reclaimed Malbec as their prize and applied rigorous natural farm practices and techniques to produce wines far more voluptuous and velvety in their youth than was exhibited by the best of their forebears.

The twelve-bottle pack offer, at $286 and all included, contains three bottles of each of the first four featured wines. Separately, we are offering a special cuvée “Géron Dadine de Haute-Serre” from Georges Vigouroux’s Château de Haute-Serre, at a deeply discounted price.

Château de Marcuès “Grand Vin Seigneur” 2015 ($28)

When he bought Château de Mercuès in 1983, Georges Vigouroux’s main focus was restructuring the vineyards on the gravely hillocks above the communes of Caillac and Mercuès; the fact that he also restored the 13th-century castle on the estate was icing on the cake. The turreted château is now hotel, where guests are encouraged to take part in the harvest and vinification process. Among the changes Vigouroux brought to the replanted vineyards was an increased vine density, a technique used by the great châteaux of the Médoc. It reduces yields and increases concentration in the wines. Like the hotel, “Grand Vin Seigneur” is luxurious and supple behind a solid exterior. It shows cassis and black cherry beneath a granitic nose, with wood smoke and black pepper at the finish.

When he bought Château de Mercuès in 1983, Georges Vigouroux’s main focus was restructuring the vineyards on the gravely hillocks above the communes of Caillac and Mercuès; the fact that he also restored the 13th-century castle on the estate was icing on the cake. The turreted château is now hotel, where guests are encouraged to take part in the harvest and vinification process. Among the changes Vigouroux brought to the replanted vineyards was an increased vine density, a technique used by the great châteaux of the Médoc. It reduces yields and increases concentration in the wines. Like the hotel, “Grand Vin Seigneur” is luxurious and supple behind a solid exterior. It shows cassis and black cherry beneath a granitic nose, with wood smoke and black pepper at the finish.

Clos Troteligotte “K-or” 2018 ($23)

Emmanuel Rybinsky is one of the emblematic young stars of the ‘new’ Cahors; with 29 acres planted above the fog-line—and thus, safe from mildew—he is creating terroir-driven wines from small parcels within a unique plateau of iron-rich limestone in the village of Villesèque. Planted in 1987 by Emmanuel’s father, K-or is one such plot, a mere 2.5 acre. The wine is 100% Malbec; Emmanuel gushes over the ‘bloody’ aromas, which no doubt refers to the pronounced iron minerality in the nose. This is the most aggressively aromatic wine in his collection with a smoky, roasted edge to the black currant and plum; the mouth is both savory and spicy and fronts a marvelous tannic backbone.

Emmanuel Rybinsky is one of the emblematic young stars of the ‘new’ Cahors; with 29 acres planted above the fog-line—and thus, safe from mildew—he is creating terroir-driven wines from small parcels within a unique plateau of iron-rich limestone in the village of Villesèque. Planted in 1987 by Emmanuel’s father, K-or is one such plot, a mere 2.5 acre. The wine is 100% Malbec; Emmanuel gushes over the ‘bloody’ aromas, which no doubt refers to the pronounced iron minerality in the nose. This is the most aggressively aromatic wine in his collection with a smoky, roasted edge to the black currant and plum; the mouth is both savory and spicy and fronts a marvelous tannic backbone.

Château du Cèdre “Cèdre Héritage” 2018 ($23)

Pascal and Jean-Marc Verhaeghe are brothers and collaborators. Having inherited the 67-acre Château du Cèdre from their father Charles, Pascal assumed vinification and marketing duties while Jean-Marc manages the vineyard. The estate contains two distinct soil types; limestone-rich scree and ancient, heavier alluvial deposits containing clay, pebbles (galets roulés) and sand. Like the brothers, these two terroirs function both separately and in communion, producing wines with elegance and style while maintaining the rustic earthiness of Malbec. “Cèdre Héritage” is a wine best described as energetic, saturated with lively aromatics of spice and herbs leading to an impeccable balance of tannin, acidity and forward, plush fruit.

Pascal and Jean-Marc Verhaeghe are brothers and collaborators. Having inherited the 67-acre Château du Cèdre from their father Charles, Pascal assumed vinification and marketing duties while Jean-Marc manages the vineyard. The estate contains two distinct soil types; limestone-rich scree and ancient, heavier alluvial deposits containing clay, pebbles (galets roulés) and sand. Like the brothers, these two terroirs function both separately and in communion, producing wines with elegance and style while maintaining the rustic earthiness of Malbec. “Cèdre Héritage” is a wine best described as energetic, saturated with lively aromatics of spice and herbs leading to an impeccable balance of tannin, acidity and forward, plush fruit.

Clos la Coutale 2018 ($16)

The tradition of winemaking in Cahors is much older than that of Bordeaux, with vines planted by the Romans fifty years before the birth of Christ. The Bernède family has played a significant role in this heritage, today managing a property founded before the French Revolution. To this history, however, Philippe Bernède brings innovation, and his current blend of Clos la Coutale contains as much as 20% Merlot, giving his wines its signature softness while maintaining a great potential for aging. The 148 acres he tends are blessed with an ideal, southwest-facing microclimate while the vines are rooted in soils rich in siliceous, clay and limestone. The 2018 shows plum, cherry and blackberry pie nestled in chewy tannins with a long, luxurious finish. Speaking of innovation, you’re welcome to open this bottle with the spring-loaded, double-hinged corkscrew patented by Bernède in one of his many guises, one as an inventor.

The tradition of winemaking in Cahors is much older than that of Bordeaux, with vines planted by the Romans fifty years before the birth of Christ. The Bernède family has played a significant role in this heritage, today managing a property founded before the French Revolution. To this history, however, Philippe Bernède brings innovation, and his current blend of Clos la Coutale contains as much as 20% Merlot, giving his wines its signature softness while maintaining a great potential for aging. The 148 acres he tends are blessed with an ideal, southwest-facing microclimate while the vines are rooted in soils rich in siliceous, clay and limestone. The 2018 shows plum, cherry and blackberry pie nestled in chewy tannins with a long, luxurious finish. Speaking of innovation, you’re welcome to open this bottle with the spring-loaded, double-hinged corkscrew patented by Bernède in one of his many guises, one as an inventor.

Special Bottle. Special Price.

Château de Haute-Serre “Géron Dadine” 2017 ($52)

Although not part of the twelve-bottle special, Château de Haute-Serre is available separately, and a Cahors label well-worthy of mention. This Georges Vigouroux selection comes from one of the highest vineyards in Cahors, and likewise, the prestigious Géron Dadine cuvée sits near the summit of Cahors quality. The terroir beneath Château de Haute-Serre is driven by mineral-packed red clay, resulting in a wine that is intensely perfumed with currant, spring flowers, tobacco and truffle. The fruit is abundant and the tannins are ripe, giving this wine the muscle to age as well as the finesse to enjoy tonight.

Although not part of the twelve-bottle special, Château de Haute-Serre is available separately, and a Cahors label well-worthy of mention. This Georges Vigouroux selection comes from one of the highest vineyards in Cahors, and likewise, the prestigious Géron Dadine cuvée sits near the summit of Cahors quality. The terroir beneath Château de Haute-Serre is driven by mineral-packed red clay, resulting in a wine that is intensely perfumed with currant, spring flowers, tobacco and truffle. The fruit is abundant and the tannins are ripe, giving this wine the muscle to age as well as the finesse to enjoy tonight.

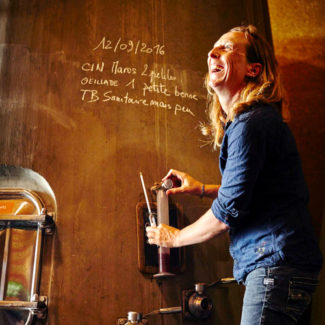

Great wines may be made in the vineyard, but the finesse is often created on the sorting table. When Sébastien Gay took over Domaine Michel Gay after his father’s 2001 retirement, among the improvements he initiated was a shift to organic farming, doing multiple “green harvests,” limiting yields by hand-pruning the vines and adding a pair of sorting tables where dozens of workers determine the quality levels of individual grapes. According to Sébastien, “Our wines show more balance now because modern techniques allow us to better control the different steps in the winemaking process.”

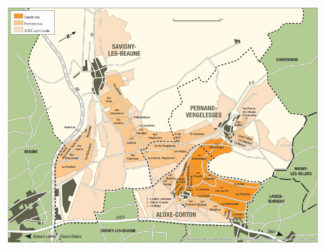

Great wines may be made in the vineyard, but the finesse is often created on the sorting table. When Sébastien Gay took over Domaine Michel Gay after his father’s 2001 retirement, among the improvements he initiated was a shift to organic farming, doing multiple “green harvests,” limiting yields by hand-pruning the vines and adding a pair of sorting tables where dozens of workers determine the quality levels of individual grapes. According to Sébastien, “Our wines show more balance now because modern techniques allow us to better control the different steps in the winemaking process.” At just over 37 acres, the estate is relatively small, but it incorporates vineyard plots in communes with storied names and spreads across a kaleidoscope of terroirs, including Chorey‐lès‐Beaune, Aloxe‐Corton, Savigny‐lès‐Beaune Premier Crus Serpentières and Vergelesses, three premier crus in Beaune, Toussaints, Aux Coucherias, and Les Grèves, as well as a small parcel on the Corton hill in the Renardes vineyard. Vines are between forty and sixty years old, and receive the same individualized attention as the grapes do at harvest. A fifth-generation winemaker, Sébastien who recently was joined by his son Laurent, has embraced modernity while revering tradition and the result is a portfolio of wines that see improvement with nearly every vintage.

At just over 37 acres, the estate is relatively small, but it incorporates vineyard plots in communes with storied names and spreads across a kaleidoscope of terroirs, including Chorey‐lès‐Beaune, Aloxe‐Corton, Savigny‐lès‐Beaune Premier Crus Serpentières and Vergelesses, three premier crus in Beaune, Toussaints, Aux Coucherias, and Les Grèves, as well as a small parcel on the Corton hill in the Renardes vineyard. Vines are between forty and sixty years old, and receive the same individualized attention as the grapes do at harvest. A fifth-generation winemaker, Sébastien who recently was joined by his son Laurent, has embraced modernity while revering tradition and the result is a portfolio of wines that see improvement with nearly every vintage. Corton-Renardes Grand Cru “Vieilles Vignes” 2016, $145

Corton-Renardes Grand Cru “Vieilles Vignes” 2016, $145

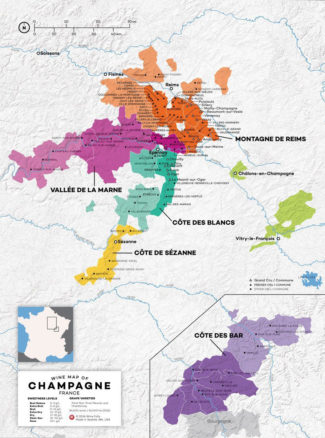

At its essence, ‘cru’ refers to real estate; its evolution as an often-appearing designation onFrench wine labels is meant to be a nod to the ‘sense of place’ that is fundamental to the concept of ‘terroir.’ But in France, not all crus are created equally. In Burgundy, for example, a cru signifies a vineyard; in Bordeaux, it refers to a chateau or an estate. In Champagne, a cru encompasses an entire village and is based on the classification system adopted in 1920. The Échelle des Crus ranked the more than 300 wine-producing villages in Champagne according to a quality potential based on overall growing conditions and was made manifest primarily by the prices each commune could charge for a kilogram of grapes. In the original classification, 12 villages were rated as Grand Crus (expanded to 17 in 1985) and were entitled to receive 100% of the pricing set by the Champagne appellation for their harvest; 44 were Premier Crus and commanded 90 to 99% of the pricing, and the remaining named villages could charge 80-89%, with none rated lower than that. A bottle may only use the term ‘Grand Cru’ if 100% of the grapes used are from Grand Cru villages, while a bottle labelled ‘Premier Cru’ must be 100% Premier Cru or a mix of both Grand and Premier.

At its essence, ‘cru’ refers to real estate; its evolution as an often-appearing designation onFrench wine labels is meant to be a nod to the ‘sense of place’ that is fundamental to the concept of ‘terroir.’ But in France, not all crus are created equally. In Burgundy, for example, a cru signifies a vineyard; in Bordeaux, it refers to a chateau or an estate. In Champagne, a cru encompasses an entire village and is based on the classification system adopted in 1920. The Échelle des Crus ranked the more than 300 wine-producing villages in Champagne according to a quality potential based on overall growing conditions and was made manifest primarily by the prices each commune could charge for a kilogram of grapes. In the original classification, 12 villages were rated as Grand Crus (expanded to 17 in 1985) and were entitled to receive 100% of the pricing set by the Champagne appellation for their harvest; 44 were Premier Crus and commanded 90 to 99% of the pricing, and the remaining named villages could charge 80-89%, with none rated lower than that. A bottle may only use the term ‘Grand Cru’ if 100% of the grapes used are from Grand Cru villages, while a bottle labelled ‘Premier Cru’ must be 100% Premier Cru or a mix of both Grand and Premier.

Highlighting a specific cru is also somewhat rare in Champagne, where cuvées are generally blends of plots from several villages. With “

Highlighting a specific cru is also somewhat rare in Champagne, where cuvées are generally blends of plots from several villages. With “

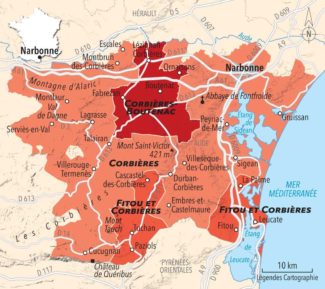

“La Boulière”, Fitou 2015 ($32.00) – 333 cases produced – (Mourvèdre 50%, Carignan 25%, Grenache 25%) Elegant old-vine cuvée showing dried cherries, figs, light tobacco; full-bodied, ultra-polished, layered and balanced package; much livelier than many Mourvèdre-based wines from nearby Bandol.

“La Boulière”, Fitou 2015 ($32.00) – 333 cases produced – (Mourvèdre 50%, Carignan 25%, Grenache 25%) Elegant old-vine cuvée showing dried cherries, figs, light tobacco; full-bodied, ultra-polished, layered and balanced package; much livelier than many Mourvèdre-based wines from nearby Bandol.

“Retour aux Sources”, Fitou 2016 ($30) – 583 cases produced – (Carignan 45%, Lladoner Pelut 30%, Mourvèdre 25%): Carignan we know; Lladoner Pelut may be less familiar, even to wine fanatics. Believed to be a mutation of Grenache Noir, ‘pelut’ is French for ‘furry’ and makes a reference to the vine’s downy leaves, likely evolved to retain moisture and regulate transpiration. Roughly 70% of the wine is matured in concrete vats and the rest in old barrels, offering jammy fruit, excellent structure, and heady aromas of ripe blackberries and herbs, making a wine ideal for hearty vegetable dishes like ratatouille and olive tapenade.

“Retour aux Sources”, Fitou 2016 ($30) – 583 cases produced – (Carignan 45%, Lladoner Pelut 30%, Mourvèdre 25%): Carignan we know; Lladoner Pelut may be less familiar, even to wine fanatics. Believed to be a mutation of Grenache Noir, ‘pelut’ is French for ‘furry’ and makes a reference to the vine’s downy leaves, likely evolved to retain moisture and regulate transpiration. Roughly 70% of the wine is matured in concrete vats and the rest in old barrels, offering jammy fruit, excellent structure, and heady aromas of ripe blackberries and herbs, making a wine ideal for hearty vegetable dishes like ratatouille and olive tapenade.

“g Grenat”, Rivesaltes Grenat (Vin Doux Naturel) 2015 ($26), 375 ml – 258 cases produced – (Grenache Noir 100%) A naturally sweet wine produced by harvesting grapes at maximum ripeness, then macerating them without fermentation by the addition of neutral spirits. The wine is fresh and full of jellied fruit with a hint of cocoa, with just enough tannin and acidity to avoid being syrupy. It makes a fine dessert on its own or paired with dried fruit, salted nuts, chocolate and fresh cheeses.

“g Grenat”, Rivesaltes Grenat (Vin Doux Naturel) 2015 ($26), 375 ml – 258 cases produced – (Grenache Noir 100%) A naturally sweet wine produced by harvesting grapes at maximum ripeness, then macerating them without fermentation by the addition of neutral spirits. The wine is fresh and full of jellied fruit with a hint of cocoa, with just enough tannin and acidity to avoid being syrupy. It makes a fine dessert on its own or paired with dried fruit, salted nuts, chocolate and fresh cheeses.

Domaine de Montcalmès

Domaine de Montcalmès Domaine Saint Sylvestre

Domaine Saint Sylvestre Mas Jullien “Lous Rougeos”

Mas Jullien “Lous Rougeos” Mas Cal Demoura “Terre de Jonquières” (2017) $32

Mas Cal Demoura “Terre de Jonquières” (2017) $32 Le Clos du Serres “Les Maros”

Le Clos du Serres “Les Maros” Château Lafite-Rothschild (Pauillac) First Growth

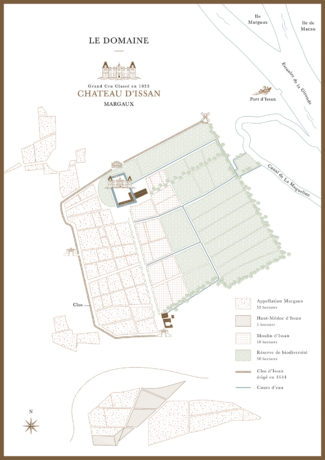

Château Lafite-Rothschild (Pauillac) First Growth Château d’Issan (Margaux) Third Growth

Château d’Issan (Margaux) Third Growth